Working with wood: Eske Rex

In a new series of articles, The Mindcraft Project focuses on some of Denmark’s influential designers and makers seen through the eyes of UK-based design, craft and architecture writer Grant Gibson.

In this article Grant Gibson meets Eske Rex.

Just for a moment Eske Rex is lost in the poetry of his process and his fascination with wood. “I pick up a piece of timber from the saw mill and I take it back to the studio. I do one cut and then I steam it and unfold it. When I do that I can feel the forces within it and what is hidden inside. I can’t control the unfolding. It’s about how thin the wood is or how thick; how long the cut is. Every single one is different.” He’s describing the ‘unfolded plank’, one of a number of motifs that run through a practice, which sits satisfyingly somewhere between art, design and craft.

Interestingly, he alighted upon his material of choice for deeply personal reasons. “It wasn’t so much about the wood, as it was about working with my Dad,” he tells me over Zoom, his voice still hoarse as he recovers from Covid. His parents separated when he was a child and spending time with his father became precious. “That was my space with him. We didn’t need to speak so much but we could create something. At that point, I wasn’t focused on wood and thinking it could do all kinds of stuff.”

Nevertheless, he became a carpenter, working mostly on houses, and creating furniture pieces for his flat in the evening. It’s still something he does to this day but, by the same token, he didn’t feel entirely satisfied and was keen to scratch a creative itch. As a result he won a place at the design school of The Royal Danish Academy. While he was there, he worked in an array of materials but still found himself being drawn inexorably towards wood. “I’ve just got this love for wood somehow. It’s the material I know best and it’s the material I like to work in,” he says.

Rex started developing the piece that brought him to international attention in his final year as an undergraduate. When ‘The Drawing Machine’ launched in Milan as part of The Mindcraft Project 2011, it took up an entire basement. The piece consisted of two timber pyramid-shaped, towers weighted by pendulums, with a pair of arms holding a pen. As the pendulums swung the pen drew shapes across a huge piece of paper. “I was very interested in building something at a scale where you could interact with your body. You could feel things with your whole body, not just your fingers,” he says. Initially, his first iterations of the machine were significantly smaller and his notion was to turn the two dimensional drawings they produced into three dimensional pieces of furniture or architectural models. It was only after graduating, when he was invited to exhibit in a show, entitled Designers Investigate, that he decided to concentrate on the process rather than attempting to produce finished objects.

Subsequently, he became something of a fixture with the Mindcraft installation. The year after he was given a brief to ‘connect’ the two walls of the exhibition. As a result he came up with Space Meter, a 6 metre long wire positioned above visitors’ heads that finished with a wooden funnel. The piece was held in place magnetically. This led to his ongoing investigation, entitled Divided Self, where two halves of a wooden object are suspended – one from the floor to the other from the ceiling. The pieces are attracted by embedded magnets, yet prevented from joining by the length of the wire to which they’re attached. “They’re strong and they’re really fragile,” Rex explains. “You can feel this tension, which is the magnetic force.”

It’s an idea he returns to periodically. “I can leave it for six months or two years, come back to it and approach it in a different way. The concept is kind of the same but I can do a new series, with new ways of shaping the objects.”

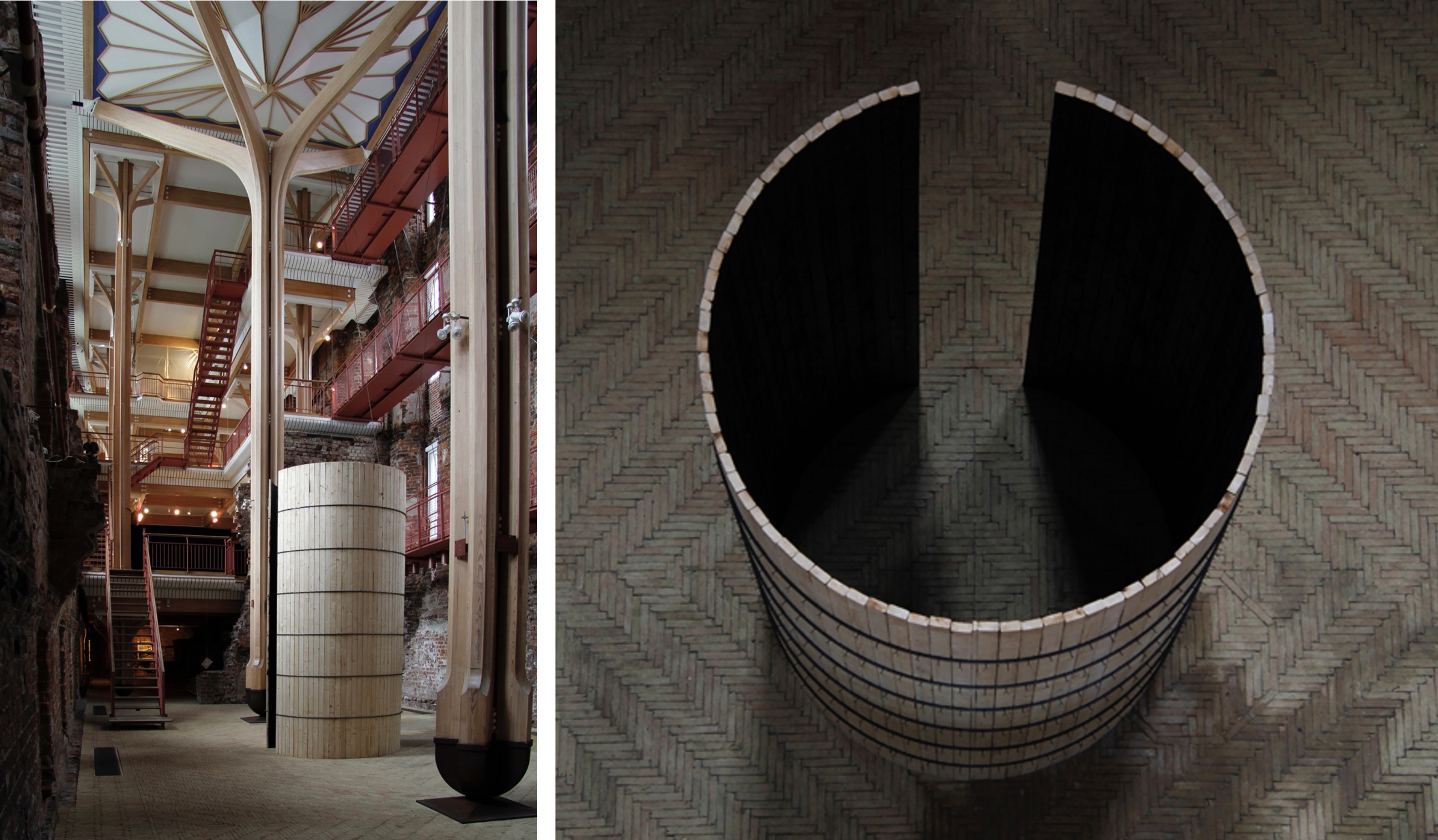

Working with space is another recurring theme. In 2014, for instance, he created Retrium, a large silo, made from spruce, in the south wing of Koldinghus Castle. The artist referenced a fire that destroyed the building in 1808 by charring the piece’s interior. “When you interact with a specific site, it’s more interesting to answer the questions there, and what the space tells you, than to simply place a design idea,” he says.

Are there links in a portfolio that, at a glance, can look a little disparate? Well, there’s the importance of scale, a sense that his work is often trying to capture, or at least play with, volume. And, of course, there is his fascination with wood. Much of this comes back to his days of house building, as he’s happy to acknowledge himself. “I’m a carpenter in my heart but also I’m a designer,” he tells me, as our conversation winds to a close. “Somehow if I’m only doing carpentry, I miss those moments where I create stuff. And if I’m only doing the design, and trying to figure out the meaning of it, then sometimes I can’t really find my way. I need to do something specific. Hence the carpentry. It’s keeping me healthy to have this duality.”

Grant Gibson was previously editor of Blueprint and Crafts magazines, and his work has been published in The Observer, The Guardian, Daily Telegraph, FRAME and Dwell. In 2019, he launched the critically acclaimed podcast series Material Matters with Grant Gibson.